2025 Hindsight: Still feels overwritten sadly, but there is an idea here - ‘how does the development system of modern big tech adapt to checking for vibes’? Of course we know the answer now in the context of LLMs, but chalk another one up to Mystic Modha I guess, given tha this was 2021…

Models are everywhere now. So many products we use have moved on from hand-tuned heuristics (if email contains 'viagra' then spam = 1) to programs that haven’t actually been programmed at all, but taught to do a job, as Ben Evans puts it, like a million interns.

In the early days getting a system like that to work at all (in production, at scale, with reasonable serving latency) was hard enough, but now that the process of assembling the data and training the model is relatively straightforward, a whole new set of considerations emerge. How do you organise a digital product team to train the right kind of model? What style do we want the model to have? What character? How do you even evaluate something like that with consumers, let alone identify an opportunity for one?

Models with personalities?

Some examples to mull over

In the days when we all still travelled by taxi, I could usually tell, without looking, what app the driver was using for their navigation. If it was taking us down insane shortcuts, keeping us moving at all costs, at the risk of nausea or worse, then it was definitely Waze. If, on the other hand, the route was just garden variety cabbie, with some odd choices but nothing teeth chattering, then most likely Google Maps. And if there were some, ahem, quixotic choices, then perhaps the Uber app itself.

(I never saw a cab driver using Apple Maps, though, heretically, I quite like it myself, especially with one of the new American voices - makes it easier to accept when it puts the emphasis in the wrong place when pronouncing peculiarly British road names like the B256.)

The great grandaddy of recommenders - Amazon’s original collaborative filtering algorithm - had an interesting tuning parameter. At one point you have to divide through by a number. If you divide through by a particular number then you get really weird-ass obscure recommendations. If you divide through by 1 (i.e. leave it unchanged) then you get really boring ones because you end up recommending popular stuff to everyone (Harry Potter for example) regardless of whether they are buying ratchet screwdrivers or screwball tumblers.

But if you divide through by the square root of that term then you get a nice balance - stuff that’s interesting enough to be usefully related, but no so obscure that people get confused. Or as they put it in the article:

Relatedness scores need to strike a balance between popularity on one end and the power law distribution of unpopular items on the other.

Really, this is an early example of choosing a personality for a model. Right there at the start - did they want Amazon’s suggestions to feel sensible and generic, or toothsome and interesting but perhaps a bit odd?

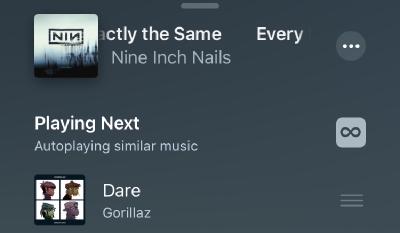

The aforementioned lemniscate. There are a number of recommendation systems in Apple Music - it does some automated playlists based on what you listen to and all that jazz (quite a lot of jazz in my case actually) - but the infinity symbol is a product that gets triggered whenever you ask for a single track of something. If the ‘button’ is pressed, then it tries to carry on and play more stuff with the same ‘vibe’.

That way, if you say ‘Hey Siri play that obscure track which has suddenly popped into my head’ (Siri’s getting good these days dontcha know) it will play the song and then try to follow suit. As far as I can tell it is a different model from the one that does the ‘Hey Siri play a radio station based on “Whigfield Sturday Night”’ (don’t try that at home kids) and it just feels a lot better. I usually find the radio station style one irritating at best, but our lemniscate friend just seems to know what I’m in the mood for, and what I like about the track I ordered up.

To me, it feels like mixtape from enthusiastic muso friend - affectionate, enthusiastic and slightly wonky-in-a-good-way. It seems to be paying attention to musical factors quite a lot - similar instrumentation or distinct percussion - but then also does some lovely lateral moves, taking me places that I wasn’t expecting but enjoyed visiting.

Product silos

That’s the user experience. But now imagine being the product team behind that l’il old button.

Firstly you’ve got some really tedious shit to deal with. It’s got to work in multiple languages, respect different catalogue availability, be aware of age restrictions for the user, and so on and on. You’ve got to make the UI work on multiple surfaces from the Apple Watch screen through to a giant iMac and the various handoffs - it’s the Apple Watch but controlling playback on some other device, which in turn is Airplay-ing to something else that gets its stream data straight from the servers. Yadda yadda yadda - all pretty dull.

And then you’ve got to try and do voice recognition and parsing of the strings efficiently as well - which is really tricky with music because ‘play Jamie Cullum Marlon Brando’ means the track ‘Marlon Brando’ by artist ‘Jamie Cullum’, but ‘Marlon Brando’ is also an artist, because of the Guys and Dolls soundtrack, and you really don’t want to confuse those two.

And once that’s sorted you’ve got the organisational challenges as well. There’s a classical research team who do surveys and stuff and ask people what they think. (And people sometimes tell them the truth, or at least the truth at the time they are doing the survey, rather than after two gins at home with their feet up, scratching the cat behind the ears and waiting for Just Eat, which is really when it matters what track comes Up Next)

Then there’s a UX team who do deeper, typically more qualitative research, but often still in fairly artifical settings. And the UX Designers who have plenty of ways to mock up how it would look, but nothing to help wireframe personality; to mock up how its behaviour should feel.

And there’s a product analyst who is supposed to be building benchmarks for overall growth of the product but might be persuaded to knock out some a/b tests on the side.

And the software engineers, who in this instance probably love music, and perhaps some machine learning engineers as well, who will both be doing some ’testing’ of their own. Finally, in the Apple case at least, you’ve got a whole load of MaaS (Musos-as-a-service) who can tell you what they would recommend, if only you could tap their expertise in a way that gave you thousands of clean, consistent training examples.

And across this siloed mix of specialists, you, dearest junior product manager number 3, have to try and craft something as slippery as a style of track recommender, and get all these different specialists to work together to produce it, even though they have scarcely any common professional vocabulary between them. You need to identify white space among all the other recommenders you’ve got going in product, articulate what’s different about this one enough to get sign off, get it made, test it, tune it and maybe someday ship the bastard as well.

Is it any wonder it’s hard to make a good button these days?

Closing Loops

Which is why I think it’s sometimes easier for indie developers to make good stuff - they have so much more freedom, and they can just tune the product to suit themselves. Or mutatis mutandis it is why sometimes the best stuff comes out of hackdays - people just making things to suit themselves and getting it to a point where other people can see a life beyond the scrappy, pizza-and-caffeine-powered pilot in front of them.

But to do it more systematically, I think that would be the interesting challenge - to find ways of analysing the product data in ways that the UX people and researchers could have a feel for; find ways of interpreting existing models and sharing that with your tame musos to understand why the models work so well; to find ways that the qualitative, the slippery, the ethereal and yes, dammit the numinous, can rub shoulders with the tensors and vectors and the kernel tricks and the millions of parameters on a basis of mutual understanding and appreciation.

Is that too much to ask? Do you know anyone who makes digital products in that way? Perhaps you should ask the people who made my next top model.

Footnote

In writing this I had some other examples left over, of places where have engineers forced the direction of development because of their empathy with people. Where they have seen a connection between complex technical work and simple human needs.

- Page/Brins obsession with speed of response

- Qualcomm’s Joseph pushing for CDMA just because…

- Maybe Chesky in engineering trust around AirBnb

- Maybe BlackBerry and the way they tamed a slow, dirty connection by empathising with the way that people used the devices